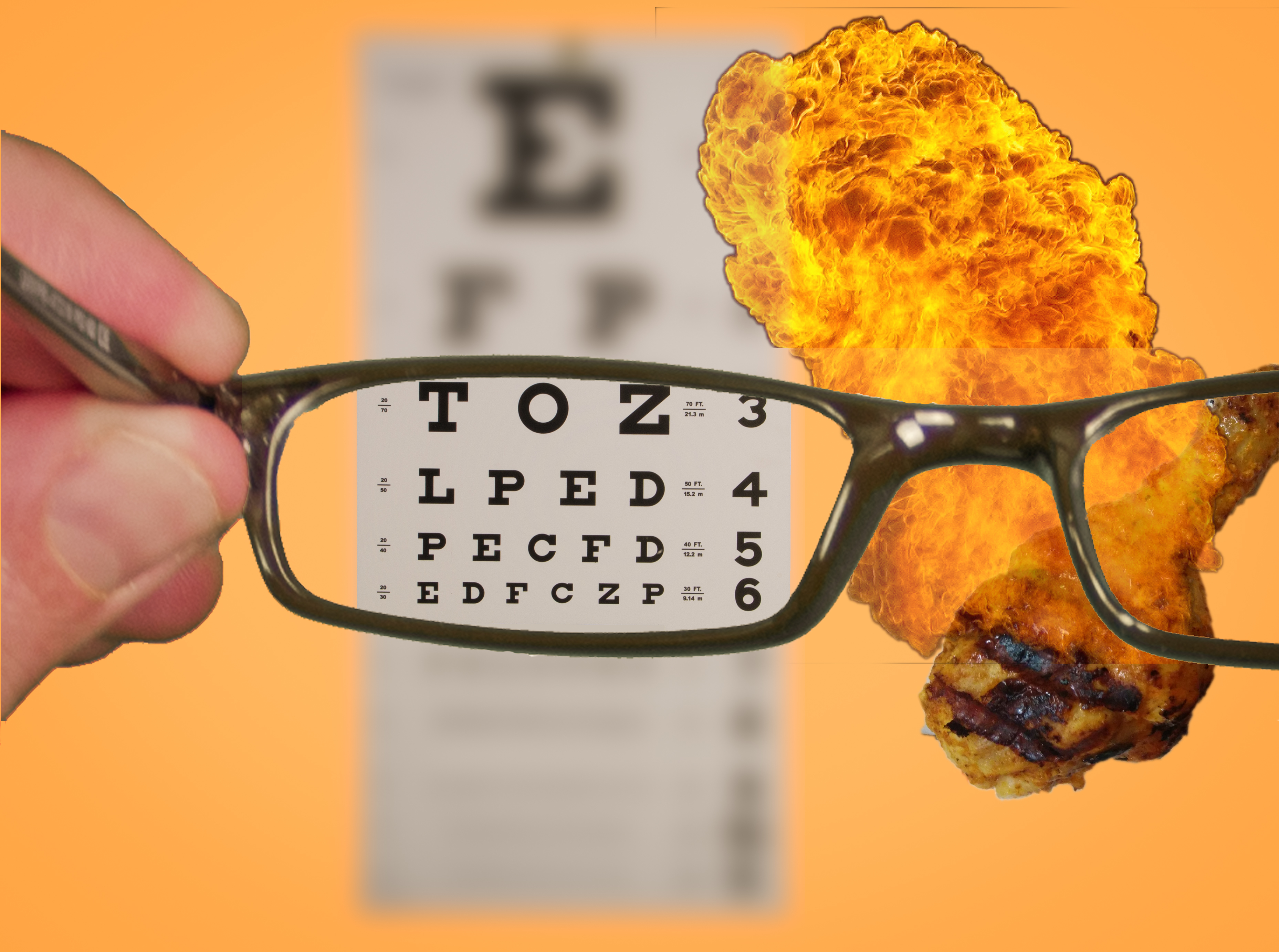

My father once remarked that after years of eye exams, he had memorized the eye chart. This level of mastery of the material would guarantee success on an algebra or biology test, but it is not helpful in an eye exam. Unlike other tests, the goal in an eye exam is not to give the objectively right answers, correctly identifying the blurry letters on the chart, but rather to report how they subjectively appear.

As difficult as discerning the tiny letters may be, discerning the proper way to face moral and life decisions can be even more daunting. This is especially true when one has trouble discerning exactly what this word “discernment” means. Some explanations give the impression that discernment is a foolproof process which, by introspectively consulting the conscience, infallibly delivers God’s will for any situation. In this view, like in eye exams, the key is being true to your perception. Yet, this view is only half true: we are indeed bound to follow our conscience, reason’s judgment about whether an action is right or wrong, but that doesn’t mean its judgments are always correct (CCC 1786, 1790).

These two truths about conscience lead to a striking conclusion: a faulty conscience can bind us to do something objectively wrong! How can this be? Suppose a mother leaves a note for her son: “Put the chicken in the oven at 4:45 P.M. at 350°.” Finding the note when he returns from school, he squints at it, reads “Put the chicken in the oven at 2:45 P.M. at 450°,” does so, and then goes upstairs to study diligently. Was the son disobedient to his mother?

In his intention, certainly not; his aim was to obey his mother’s instruction, as he could best discern it with his defective eyesight. If he had done anything other than what he thought she had asked him to do, perhaps disdaining her lack of culinary expertise, even if it happened to be what she actually had written, that would have been willful disobedience. Yet, even if the son is not guilty of disobedience, the mother, upon returning home, will certainly not be pleased to find the burnt ashes of dinner. Clearly, there is a problem that must be fixed: an eye exam and some new glasses are in order.

Burning dinner to a crisp is never good. Indeed, it is never good to do any evil action. Nevertheless, an erring conscience may bind us to do something objectively evil but subjectively perceived as good, for to act against the judgment of conscience is itself a self-contradictory act, setting one’s will against one’s (faulty) reason (Summa theologiae, Ia IIae, q. 19, a. 5). In such a situation, one’s subjective guilt may be minimized (CCC 1793), but the result still is as problematic as a burnt chicken.

Doing something with a good intention is necessary for any action to be good. Yet it is not sufficient. If we want to do good, we must not only follow our conscience, but also seek to form our conscience to recognize what is truly good. This allows us to grow in the virtue of discernment. In a private revelation from God recorded in her Dialogue, St. Catherine of Siena received a wonderful definition of this virtue:

“Discernment is nothing else but the true knowledge a soul ought to have of herself and of me, and through this knowledge she finds her roots.”

— The Dialogue of St. Catherine of Siena, 9

The spectacles of discernment that clarify our choices are not some infallible introspective process, but rather the virtue of seeing everything in light of Who God Is and who we are. For St. Catherine, this light is summed up by God’s repeated message to her: “I Am He Who Is, you are she who is not.” God alone is infinite and exists necessarily, all created things are finite and continue to have their being only thanks to His great, loving generosity. Consequently, nothing, no benefit to created beings, can ever justify offending the infinite God through sin:

“That love would be lacking in discernment which would commit even a single sin to redeem the whole world from hell or to achieve one great virtue.” — The Dialogue of St. Catherine of Siena, 11

With this principle of discernment, constantly reaffirmed by the Church (CCC 1789, Humanae vitae 14), the correct path in so many moral situations becomes clear: do not do evil. At times, we may be tempted to set this principle aside, to obtain some greatly desirable good through some seemingly small evil. But if the chicken-burning boy already had glasses and refused, against his mother’s insistence, to wear them, then he would certainly be culpable for the burnt bird, as we would be by setting aside this wonderful principle of discernment (CCC 1791).

But who would want to refuse the vision given by this knowledge of God and self, a vision which frees us to live a life flowering in virtue, not one of calculated evildoing, but a life of simply following the exhortation of the Psalmist:

Tremble, do not sin: ponder on your bed and be still.

Offer right sacrifice, and trust in the LORD.

— Psalm 4:5-6

✠

Image by Br. Isidore Rice, O.P.